BRB Bottomline: In response to the housing crisis Berkeley experienced seventy-five years ago, former UC President Robert Gordon Sproul stated that “The gravity of the situation cannot be overemphasized.” Seventy-five years later, Berkeley is entrenched in another housing crisis affecting tens of thousands of people. While the exact causes are debatable, many accuse ineffective government policies in response to a fast-growing population. The repercussions of this housing crisis have taken a toll on Berkeley residents, resulting in rampant housing insecurity and a vulnerable, increasing homeless population.

Why Study Abroad?

In response to the housing crisis Berkeley experienced seventy-five years ago, former UC President Robert Gordon Sproul stated that “The gravity of the situation cannot be overemphasized.” Seventy-five years later, Berkeley is entrenched in another housing crisis affecting tens of thousands of people. While the exact causes are debatable, many accuse ineffective government policies in response to a fast-growing population. The repercussions of this housing crisis have taken a toll on Berkeley residents, resulting in rampant housing insecurity and a vulnerable, increasing homeless population.

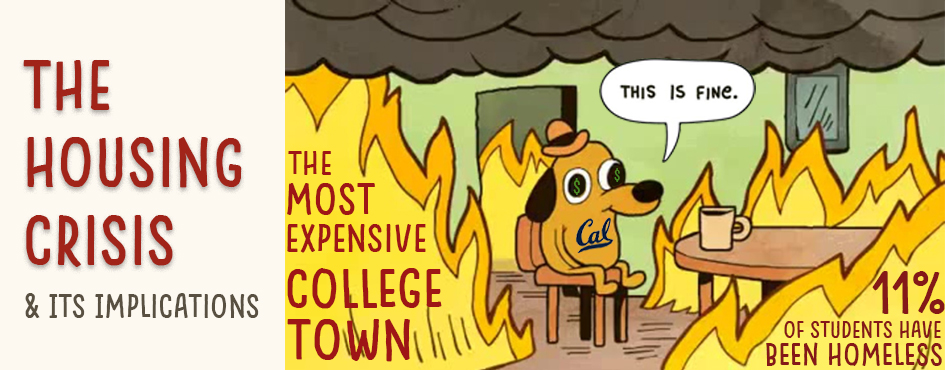

Berkeley is ranked the most expensive college town in the United States with the median house price at $849,000 and the cost of necessities averaging $81,621, according to Business Insider. These stats, however, don’t paint the whole picture. Walk through Berkeley and the homeless population becomes immediately obvious. It’s an issue made even more salient when we realize that up to 11% of UC Berkeley students have either been homeless in the past or currently are. This article addresses the possible policies behind the crisis, its critical ramifications, and, finally, possible solutions.

Possible Reasons to Blame

Since 2005, the city of Berkeley’s population has increased by over 20%. This can be attributed to a couple of factors, first of which is increasing student enrollment. During the 2018 fall semester, 42,519 undergraduate and graduate students were enrolled, an increase of 7,368 from the 2013 spring semester. As the university continues to admit more students to meet the demand of a top public university, the infrastructure and housing built around campus struggle to sustain the influx. Coupled with spillover from the San Francisco housing crisis, Berkeley’s population continues to surge.

Despite the drastic increase in population, the number of buildings built has not been proportional. Yet the problem is not necessarily because of strict municipal regulations on new buildings. Compared to many other suburban municipalities such as Palo Alto, Berkeley’s construction regulations are actually less strict. In fact, from 2014 to 2017, 910 housing units were built. Berkeley’s mayor, Jesse Arreguin, further emphasized that there are “4,000 apartments in the pipeline” and “modified zoning regulations to encourage greater downtown density.” The problem, however, stems from the fact that all of this construction has taken place in the past couple of years when it should have been taking place over the past thirty years.

Some argue that this problem is further exacerbated by legislation, specifically the Costa-Hawkins Act, which essentially keeps cities from enacting rent-control policies on certain housing units. While many of Berkeley’s housing units currently have rent control, this act keeps the city from applying the policy onto even more units. Critics claim that the Costa-Hawkins Act keeps cities such as Berkeley from protecting their tenants from astronomical rent prices. They see unregulated housing as open to abuse by landlords, and they believe that some system of checks and balances is needed to maintain equal footing in the housing market.

On the other side of the debate, it is widely accepted in economics that rent control can often bring about unintended problems. For instance, Berkeley economist Kenneth T. Rosen argues that Proposition 10, a recently rejected ballot initiative to repeal the Costa-Hawkins Act, would have led to three major consequences: firstly, many residential rental units would be converted into non-residential buildings that can command higher rents. Secondly, the construction of further housing developments would be disincentivized. And, lastly, housing would be inefficiently allocated.

After all, rent control is effectively blind. It doesn’t prioritize lower-income people over high-earners, so apartments with rent-control do not necessarily go to the people they were meant to help in the first place. While the intentions behind rent control are admirable, oftentimes rent-controlled units just go to tenants who could pay a higher rate. Affordable housing is snatched away from those who need it.

The basics of economics dictate that supply will be severely reduced as a result of lower prices, intensifying the problem even more. Still, while there are obvious long-term tradeoffs to rent control, supporters of Proposition 10 do have a point—at-risk tenants must receive some form of protection now.

Problems

The lack of affordable housing has put poorer students at a greater disadvantage than they would face otherwise; expensive housing has forced many to take up part-time (or even full-time) jobs to pay for the basic costs of living. Juggling a job and being a full-time student severely affects one’s ability to learn. Plus, the drain on time and energy that a part-time job necessitates keeps these students from joining clubs, finding research opportunities, and looking for internships (which are less reliable in pay). In addition, financial stress among students has been associated with substance abuse, weight gain, and violence.

The housing crisis has serious implications which extend to the broader community as well. One of the most prominent is the resegregation of the Bay Area. Thousands of low-income black households have been forced to move out of their neighborhoods by gentrification and rising rent prices. The California Housing Partnership found that a “30% tract-level increase in median rent (inflation-adjusted) was associated with a 28% decrease in low-income households of color.” Since 2000, the black population of Berkeley has dropped from 14,000 to 9,700. These households are then concentrated into other communities, such as Ashland and Cherryland.

This exodus spells out a myriad of problems: concentrated poverty is associated with lower educational opportunities, increased crime, and decreased life expectancy, and the problem is magnified specifically for the Berkeley housing crisis because of its intersection with race. Resegregation only compounds generational cycles of poverty and socioeconomic stratification, as low-income minorities are forced to high-crime, low-opportunity neighborhoods with limited social mobility.

Solutions

One possible solution is subsidized affordable housing specifically allocated for households that generate income under a certain threshold. Unlike rent control, this means that affordable housing would be saved for those who’d be homeless without it—helping those who need it the most.

Seventy-five years ago, the Berkeley housing crisis abated as wartime workers moved out of the area. Unfortunately, this time around, no one is expecting a sudden emigration of people. Now, the problem needs to be addressed head on with new policies and governmental action. The complexity of the issue, with its implications for socioeconomic stratification and racial resegregation, underscores the need for an informed voter population to guide the city in the right direction.

Hey Quality articles or reviews is the main to interest the viewers to go to see the web page, that’s what this website is providing danke

There is obviously a bundle to realize about this. I assume you made various nice points in features also.

Wow! This can be one particular of the most useful blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Magnificent. I’m also an expert in this topic so I can understand your hard work.