BRB Bottomline: All companies want to grow. Stock analysts criticize stagnant companies, while CEOs defend themselves by touting revenue growth, same-store sales growth, monthly active user growth, or any other relevant metric to show that they’re doing their jobs. As one Forbes writer put it, “In business, you’re either growing or you’re dying.”

The question that corporate executives must ask then is how to achieve this growth. Organic growth can be slow and difficult, so companies flush with cash often try to accelerate this growth by turning to alternative strategies.

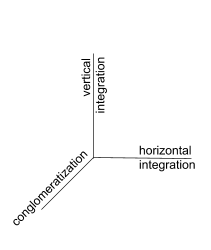

Traditionally, these faster paths to growth have been thought of in two dimensions: horizontal integration and vertical integration. In horizontal integration, companies buy their competitors; in vertical integration, companies buy other steps in the value chain (or simply develop those capabilities themselves).

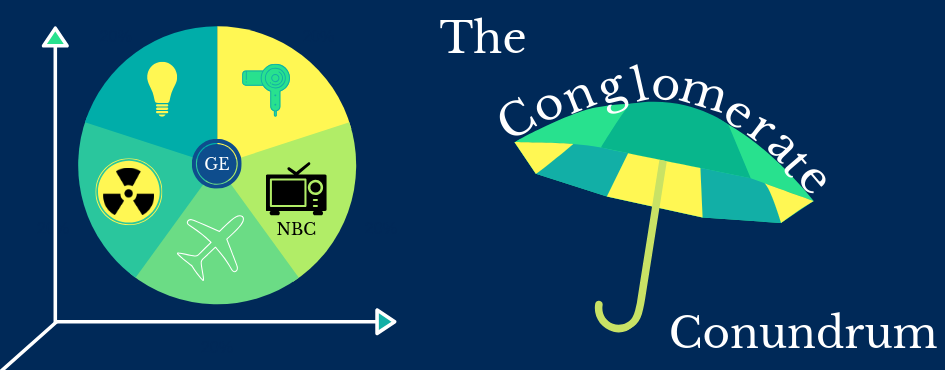

In either case, though, the opportunities for growth remain within the same industry. In this article, we discuss conglomeratization, in which a third axis (see figure below) represents a company’s opportunity set for growth outside its core industry. While conglomerates aren’t a new concept, this new three-dimensional model reveals interesting insights about how successful conglomerates grow, the pitfalls they might encounter, and the properly-constructed incentive plans that often make the difference.

Empire-Building vs. Selective Investments

Of course, not all conglomerates are created equal. There are, we must note, two very different ways to grow. The first we call empire-building, or growing for the sake of growth, and the second we term selective investment, or seeking the most efficient allocation of capital.

Both growth plans tap into the third axis of growth, but selective investment generates greater returns on invested capital (at the expense, to be fair, of higher due diligence costs and lower deal flow). Why then do corporate executives build empires? It might sound like a silly question, since we so easily attribute such actions to hubris or simple managerial inadequacy. However, financial incentive systems—the very systems intended to motivate firm-benefitting behavior—can actually create perverse pressures for managers to build empires rather than choose selective investments. To make these ideas concrete, we take a look at two conglomerates, both well-known yet very different: General Electric (GE), and Berkshire Hathaway.

General Electric

GE is a 127-year-old conglomerate that was incorporated with a focus on one industry—household electric appliances—much like most other conglomerates. However, after monopolizing the lightbulb industry by the end of the Second World War, it started diversifying into nuclear reactors, hair-dryers, and jet-turbines; it even owned the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) until 2013 and operated a financial conglomerate until 2015. GE was one of the original members of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and boasted continuous membership for over 110 years, starting from 1907. For two years between 1996 and 1997, it was also the most valuable public company in the world. However, in June 2018, it was taken off of the Dow Jones and currently trades about 94% below its peak price (reached in April 2000). Could this dramatic fall have been predicted?

The short answer is yes. The long answer is that GE’s executive compensation structure incentivized growth for the sake of growing—empire-building—rather than efficiently generating high returns on invested capital.

Financial incentives, after all, show us what a company’s board values: in this case, revenue growth above all else. Looking at GE through this lens, we see that the downfall of the company was foreseeable—and perhaps even inevitable. To further understand what happened, let’s consider the compensation structure from Jack Welch’s tenure as CEO (1981-2001), during which GE’s stock soared to incredible heights—and then plummeted right back down to Earth.

GE’s compensation structure underwent many changes during and from Welch’s tenure. Performance was incentivized through bonuses contingent on the company meeting specific financial targets; the CEO was granted Stock Appreciation Rights (SARs) annually which would have no value if the stock price on the day of vesting was lower than the price on which the grant was issued. This incentivized increasing the value of the company during the remainder of the CEO’s tenure rather than structuring GE’s portfolio based on maximizing long-term shareholder returns from each business. Furthermore, toward the end of Welch’s tenure, his bonuses were incremented because of the board’s appreciation for his “aggressive leadership,” “drive to … stretch targets,” and “boundaryless behavior” (GE’s DEF 14A Proxy Statement, 2001), making it almost blatant that the board’s incentives rewarded overconfidence and hubris.

After Welch’s retirement in 2001, Jeffrey Immelt took over as CEO. During his tenure, CEO compensation structure underwent even more transitions that led to empire-building and risky decisions. Rather than increases in his annual salary, Immelt was granted performance share units and stock options. By 2003, over 75% of his compensation, including his bonus, was contingent on performance incentive awards (GE’s DEF 14A Proxy Statement, 2003). These incentives said that if GE produced 10% growth in operating cash flows and generated higher returns than the S&P 500 over the year, Immelt would stand to earn a huge payout.

While meeting these goals might have benefited short-term shareholders, they only judged the company’s revenue over that year and neglected the company’s financial stability, its returns on invested capital, and the strategic progress of its businesses. Furthermore, since such a high percentage of Immelt’s salary depended on meeting these goals, he was incentivized to make riskier decisions that might have generated higher returns over the compensable period but not in the long run.

Additionally, Immelt was granted Restricted Share Units (RSUs) which did not vest on retirement—as was done until Welch’s tenure—but in equal annual installments over five years, thus shifting away from the company’s focus on retention until retirement to a more short-term emphasis. Simultaneously, Immelt was awarded for his growth initiatives, which reflected another transition—this one from performance, alignment, and retention to growth-focused strategic objectives such as acquisitions, joint ventures, and globalization. For instance, in 2015, GE acquired Alstom which makes coal fueled turbines used by power plants. This transaction was its biggest ever industrial purchase but represented an investment in fossil fuels, which are being replaced by renewable energy. Consequently, it had to merge this business with Baker Hughes to eventually divest it, after having overpaid for it. Moreover, from 2006, the named executives of GE, including the CEO, did not have an employment, severance, or change-of-control agreement and instead “served at the will of the board” (GE’s DEF 14A Proxy Statement, 2007). This further incentivized potentially risky strategic moves to meet growth objectives over the specified time period, rather than evaluation of the long-run potential of businesses being bought or divested during the restructuring of GE’s business portfolio.

Following this succession of self-destructive compensation structures, GE has been released from its high throne as Wall Street darling and technology innovator. Employing a compensation strategy that prioritized growth, short-term performance, and empire-building over long-term efficient value creation led to an aggressive and myopic leadership style. GE’s managers lost sight of the benefits of conglomeratization: the ability to invest wherever returns on invested capital are highest (as opposed to being constrained by the company’s core industry). This seems to be the root of GE’s downfall.

Berkshire Hathaway

Of course, we’re not arguing that growth is bad. Such a claim would be almost heretical in a market where Lyft and Spotify trade at over $20 billion valuations (primarily because of their large user bases) but continue to generate million dollar losses. Instead, we argue that growth should eschew empire-building and instead follow another principle: selective investment—in other words, directing resources to the places they generate the most efficient returns.

How is this measured? One way is ROE, or return on equity. It’s found by dividing financial returns by the equity used to generate those returns. To maximize ROE, we have to care about both the numerator and the denominator—maximizing efficiency, not just high revenues.

To understand this idea, we turn to Berkshire Hathaway, run since 1965 by the legendary Warren Buffett. Buffett’s name has become synonymous with astute investing—Berkshire’s 20.9% annualized returns since 1964 say everything—so it’s worth taking a look at his strategy.

Originally a textile company, Buffett bought Berkshire Hathaway after a perceived slight by then-owner Seabury Stanton. Stanton was quickly fired. Two years later, Buffett bought two insurance companies—National Indemnity Company and a smaller affiliate—and thus began Berkshire Hathaway’s journey to become one of the most successful conglomerates in history.

These (and other) insurance businesses have been instrumental to Berkshire’s success. In fact, the reason Berkshire has so much money to invest in other disparate companies is because of the insurance business’ massive float, a term referring to money already paid in premiums but not yet paid out in claims. Berkshire is free to invest the float generated by its insurance subsidies however it sees fit, as long as it keeps enough cash on hand to pay out claims when it has to.

For Buffett, where this money goes depends on a delicate balance between quality and price. On one hand, Buffett emphasizes that “You don’t want to buy things that are cheap. You want to buy things that are good.” On the other hand, his purchases have to be at the right price: “Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down” (2008 Letter to Shareholders).

One way to capture this balance is the ratio we discussed earlier: ROE. Even as far back as 1977, Buffett noted that “Except for special cases (for example, companies with unusually-high debt-equity ratios [where Return on Invested Capital would be a better metric because it strips away financial leverage]), we believe a more appropriate measure of managerial economic performance to be return on equity capital” (1977 Letter to Shareholders).

How, then, does Berkshire Hathaway incentivize this focus on ROE? As with GE, we can find clues in Berkshire’s compensation structure for corporate executives. According to Berkshire’s 2018 DEF 14A Proxy Statement, the Board of Directors’ Governance Committee “has established a policy that neither the profitability of Berkshire nor the market value of its stock are to be considered in the compensation of any executive officer.” This stands in stark contrast to GE’s compensation structure, in which the CEO was incentivized almost purely by how GE’s stock price grew over the compensable period.

Not only are the other executives’ salaries independent of how Berkshire’s stock performs, but Buffett and his right-hand man Charlie Munger have each only taken $100,000 a year for the past 25 years in compensation. How, then, does Berkshire incentivize growth at all?

Again, the answer lies in ROE. Buffett and Munger have a significant portion of their net worths in Berkshire Hathaway stock, so long run results really matter. When Berkshire does well, they do well. And, when Berkshire grows at a ROE above other alternatives in the market, they do better than the market. Buffett and Munger are thus incentivized to allocate capital into businesses that can generate the highest return on equity.

As for incentivizing a growth mindset in the managers that oversee Berkshire’s dozens of individual subsidiaries, the answer lies in how Berkshire constructs their salaries. Up until 2018, Buffett personally set the salaries of the CEOs of dozens of Berkshire’s significant operating businesses (the responsibilities are now split between two other Berkshire executives who still use the same general criteria as Buffett). Buffett based CEO compensation on various elements—such as economic potential and the capital intensity of their businesses—over which the CEO had control.

And again, Berkshire’s stock performance isn’t included. Buffett’s explanation? “If a CEO bats .300, he gets paid for being a .300 hitter, even if circumstances outside of his control cause Berkshire to perform poorly. And if he bats .150, he doesn’t get a payoff just because the successes of others have enabled Berkshire to prosper mightily” (2006 Letter to Shareholders).

Additionally, in an earlier letter to shareholders, Buffett noted that “When capital invested in an operation is significant, we also both charge managers a high rate for incremental capital they employ and credit them at an equally high rate for capital they release.” In other words, if a subsidiary can generate returns on capital greater than some specified hurdle rate, then it should use that capital—and the CEO would be rewarded well. But if the subsidiary can only generate sub-par returns, then the CEO should return the money to Berkshire to invest elsewhere. This “money’s-not-free approach” thus incentivizes subsidiary CEOs to only invest capital where it generates substantial returns—an efficient allocation of resources.

When corporate executives are incentivized to efficiently allocate capital toward selective investments rather than build empires, companies generate long-run value for their shareholders. These are the conglomerates that you want to identify early and hold onto for the long haul. A well-crafted compensation plan is an underappreciated but beautiful competitive advantage for any company—especially for a conglomerate.

Take Home Points

Judging whether a company is more inclined to build an empire and burn capital rather than make selective investments and build shareholder value can be difficult. Much of it depends on creating a compensation structure that incentivizes managers to build shareholder value rather than their own empires. While it’s easy for corporate executives to fall prey to hubris and blindly pursue growth at the expense of rational judgment, the right compensation structure can ensure that capital is allocated prudently and the conglomerate grows for decades.

As we close out this article, let’s take a look at Mars, Inc. If you do a little digging, you’ll soon find something interesting: yes, Mars is the maker of M&M’s, Skittles, and Snickers bars, but it’s also a leading veterinary service provider in the UK.

That unequivocally fits the description of investing beyond its core industry—the third axis of the model we proposed at the beginning of this piece. On its surface, this seems almost outrageously outlandish, but let’s not rush to judgment. What if that actually makes sense?

No, pet hospitals aren’t particularly related to chocolate candy. But maybe, just maybe, that’s the most efficient place for Mars’ capital.