BRB Bottomline: With more than $150 billion in aid distributed each year, does the money truly make it into the hands of America’s scholars?

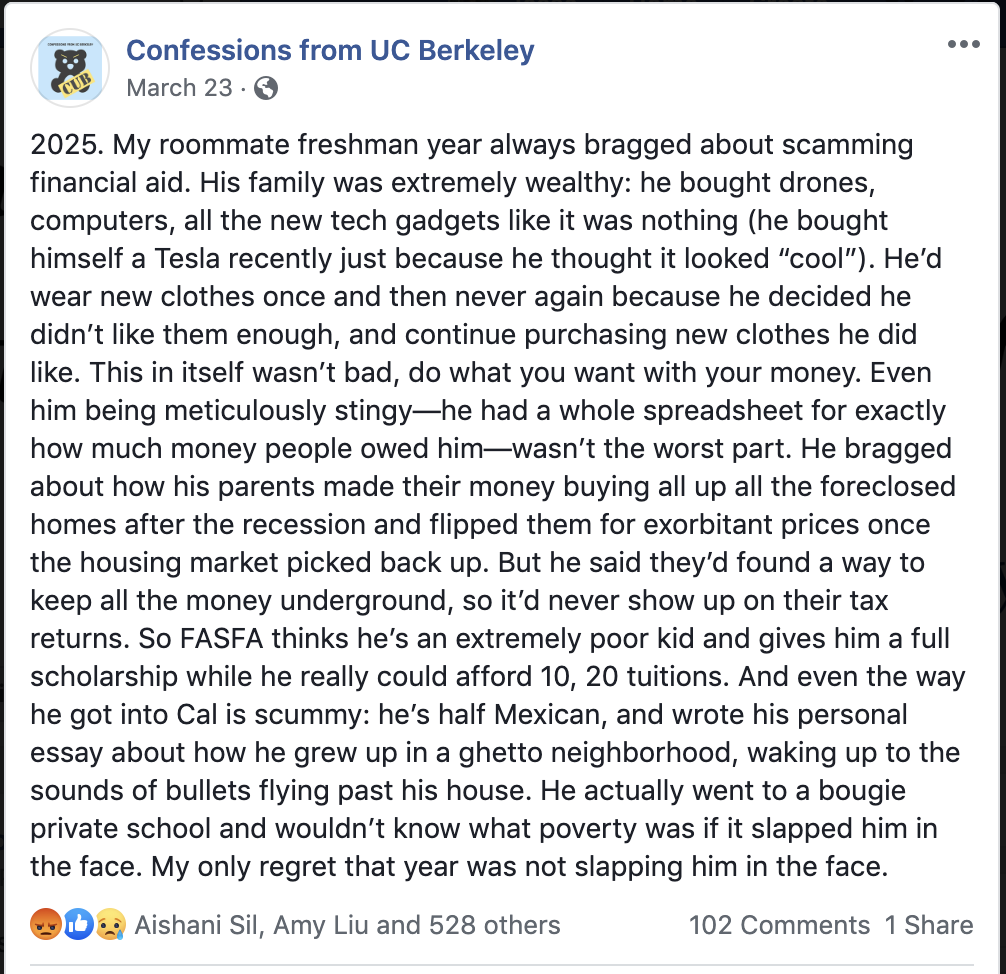

Federal and state financial aid is synonymous with opportunity for millions of students. For many, it provides the equilibrium to explore what higher education has to offer. For others, it is not nearly enough for the necessary expenses of college. Yet where there is money, fraud often follows. As much as financial aid seeks to actualize aspirations for millions of students, it can also end up in the hands of fraudsters, costing taxpayers and stealing from America’s future.

Understanding Fraud on Campus

In an effort to learn more about how financial aid verification works, I went down the rabbit hole of the financial aid process. With left turns at a range of independent auditors, right turns at loose compliance forms, and dead ends at corrupt financial aid administrations, the system showed itself as blatantly imperfect.

Schools that offer federal financial aid do so through the Title IV funding budget. In order to receive funds, schools must independently conduct or contract their own audits that verify compliance under the standards of the U.S. Department of Education. Auditing companies throughout the nation compete with one another to land contracts with schools like UC Berkeley just as much as traditional businesses. For reference, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, better known as PwC, audited UC Berkeley and the University of California in 2018.

How Much is at Stake?

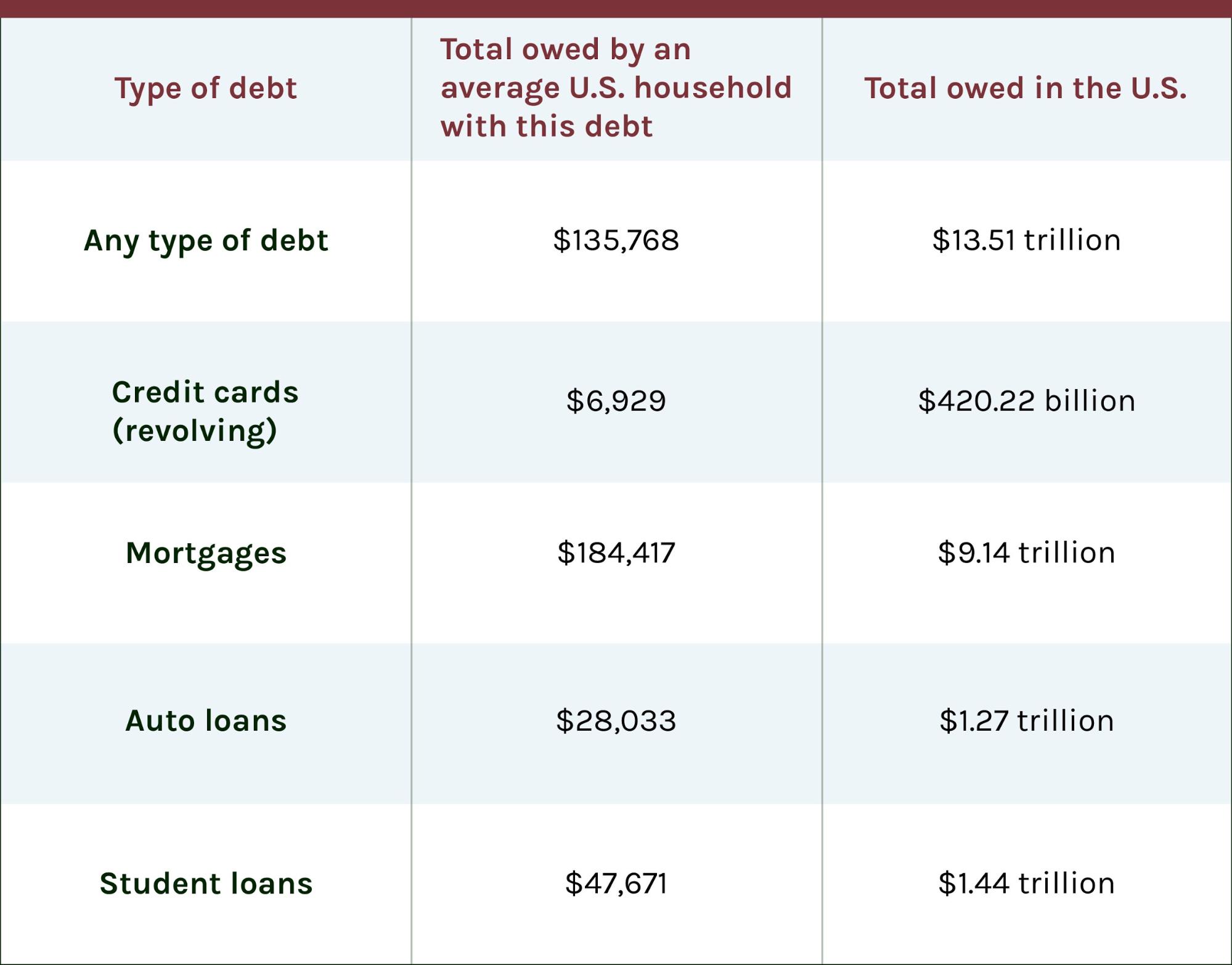

As tuition increases, more and more students are looking to rely on a subsidized education through grant programs, loans, and scholarship opportunities. 45 million Americans owe more than $1.56 trillion in student loans. Both credit card and auto loan debt—the two most common debts at $420.22 billion and $1.27 trillion, respectively—combined are still shy of the amount owed by America’s youngest population. While some of the debt is shared with independent banks, $1.1 trillion is directly owed to the U.S. government by students.

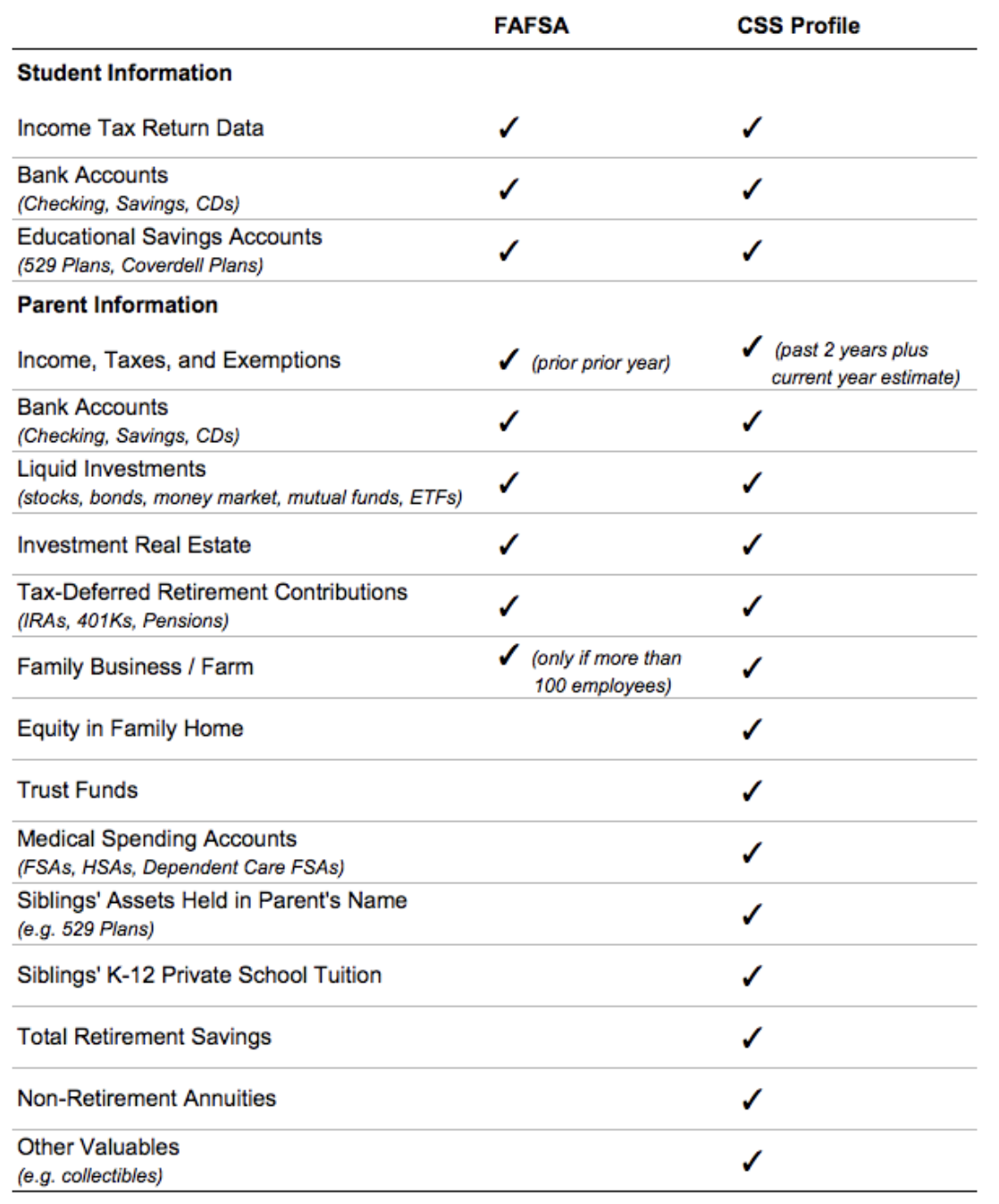

While all public universities and colleges require the FAFSA for federal financial aid, private institutions often require the CSS form in addition to the FAFSA to distribute institutional funds. The CSS form is comprehensively different because of two main aspects: firstly, it asks far more questions than the FAFSA, and secondly, it works in conjunction with the Institutional Documentation Service (IDOC) provided by the College Board. IDOC is a service where financial aid applicants directly upload tax forms, bank statements, or other required material. The two new avenues of applicant information are forwarded by the IDOC to both the university and the auditing body.

The two applications address aid differently: the FAFSA tends to be more formulaic, while the CSS profile can open additional questions tailored to individual circumstances. The CSS is thus considered a more well-rounded perspective of a student’s financial situation. Additionally, the more detailed approach of the CSS form makes it difficult to lie about one’s finances. As of 2018, the FAFSA asks all applicants 108 questions, while the CSS form can ask more than 400. Private schools are keen on ensuring the correct distribution of their funds; the information from the CSS form is then verified before distributing funds to students.

While all public universities and colleges require the FAFSA for federal financial aid, private institutions often require the CSS form in addition to the FAFSA to distribute institutional funds. The CSS form is comprehensively different because of two main aspects: firstly, it asks far more questions than the FAFSA, and secondly, it works in conjunction with the IDOC provided by the College Board. IDOC is a service where financial aid applicants directly upload tax forms, bank statements, or other required material. The two new avenues of applicant information are forwarded by the IDOC to both the university and the auditing body.

The two applications address aid differently: the FAFSA tends to be more formulaic, while the CSS profile can open additional questions tailored to individual circumstances. The CSS is thus considered a more well-rounded perspective of a student’s financial situation. Additionally, the more detailed approach of the CSS form makes it difficult to lie about one’s finances. As of 2018, the FAFSA asks all applicants 108 questions, while the CSS form can ask more than 400. Private schools are keen on ensuring the correct distribution of their funds; the information from the CSS form is then verified before distributing funds to students.

A Narrow Model: Data-Driven Probability

With such intricacies at play, the system currently relies on discrepancies in user inputted information to catch potential fraudsters. If an applicant fills certain bubbles on the FAFSA and is more eligible for aid, meaning Pell grant eligible or filing with a low income, they increase their chances of being selected for verification out of systematic suspicion that they could be a potential fraudster looking to steal a significant sum. Pell Grant recipients, a group of students who often require more financial support, have a 50% higher chance of being selected for verification. Likewise, if a user inputs inconsistent info, they will often be asked for verification.

The U.S. Department of Education (DoE) uses a risk-based model for determining which FAFSA applications are selected for verification. Those selected have their additional paperwork forwarded to an auditor. Plus, many colleges, unrequired by the Department of Education, have a policy of addressing all flagged inconsistencies before the distribution of funds, a recent trend that still not all schools follow. During the verification process, schools will crosscheck the information from tax return transcripts, proof of employment forms, and other similar documentation with the information submitted through the FAFSA.

The DoE aims to ensure that colleges accurately determine which students qualify for financial aid. At UC Berkeley, the vetting process for addressing verification often takes over a month, according to the financial aid office. Unfortunately, as a probable consequence of a lack of financial literacy, it is common for about a quarter of applicants to rescind their applications for aid upon being requested for verification.

Yet the system is imperfect and fraudsters continue to slip through the cracks. Institutional players in the financial aid ecosystem trust the verification and audit system currently established by the U.S. Department of Education. The government hires additional loan servicers with big names like Navient and Nelnet for direct student interactions and partnerships with schools. As the middlemen, they rely heavily on the validity and accuracy of school audits to make their money back. There could be a potentially devastating downside to companies like these if money is wrongfully stolen by bad players.

Solutions: Too Big to Change?

Not until only a decade ago were fraud schemes truly seen as threats to the federal government. In 2009, the first groundbreaking fraud ring was discovered when the University of Phoenix reported more than a million in losses when an employee noticed that a student’s phone number matched other student records. The identity fraud here was simple: a ring leader organized fraudsters without the intention of studying at a school to submit applications for financial aid, receive the distribution, and then make off with the money. The situation at the University of Phoenix grew as the ring of students made their way through the dark corners of financial aid auditing, accumulating thousands of dollars.

Currently, most fraud occurs at the level of financial aid administration. Those working within the system recognize the chinks in the armor and exploit millions of dollars annually. Recently, on April 9, 2019, the Director of Financial Aid at New York Graduate School, along with two former students, were sentenced for conducting a fraud scheme. The three men were ordered to pay restitution and forfeiture that totaled returning more than $3 million each. The case dealt with a falsified headcount created by the administrator at the college to pocket the generated excess in federal financial aid.

Back in March, Tyrone Dwayne Young was sentenced in federal court to more than nine years after committing student loan fraud by organizing a scheme to falsely enroll people into dozens of online universities. The restitution returned to the Department of Education totaled $1.1 million.

Former U.S. Attorney Benjamin Wagner, in distaste of fraudulent schemes these, remarked that federal student loan programs are inherently intended to “improve the long-term prospects of students committed to education” and create “a more competitive economy for the nation.” Bad players steal from America’s future.

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for the Department of Education is the directing body in investigating fraud. A 2013 report by the OIG revealed that more than $200 million in financial aid had been lost to fraud. With more than 6,000 colleges and universities and 5,000 charter schools, verifying the legitimacy and fraud prevention capabilities of every institution is an incredible task for a small government body that often faces federal sequestration. That same 2013 report also marked an 82% increase in fraudulent activity over two years. Currently, only about 90 federal investigators are in charge of seeking fraud in the education system—a starkly inadequate number compared to the scale of potential fraud in America’s education system.

Take Home Points

Fraud exists at every level, be it administrators looking to funnel and pocket money, students looking to owe less in the future, or outside fraudsters creating rings of fake identities. The system is clearly inefficient. The Department of Education must move to mandate uniform safeguards against fraud at all institutions. As more scholars seek a college degree, the scarce budget allocated for financial aid must be correctly distributed. Currently, the UC system under the Office of the President conducts a financial aid specific audit once every three years. While a full proof system may never be possible, the current one is inept at handling fraud effectively. For now, the OIG’s hotline is available for anyone who knows of or suspects “fraud, waste, abuse, mismanagement, or violations of laws” involving the funds of the U.S. Department of Education.