Author: Keshav Kumar, Graphics: Akanksha Roy

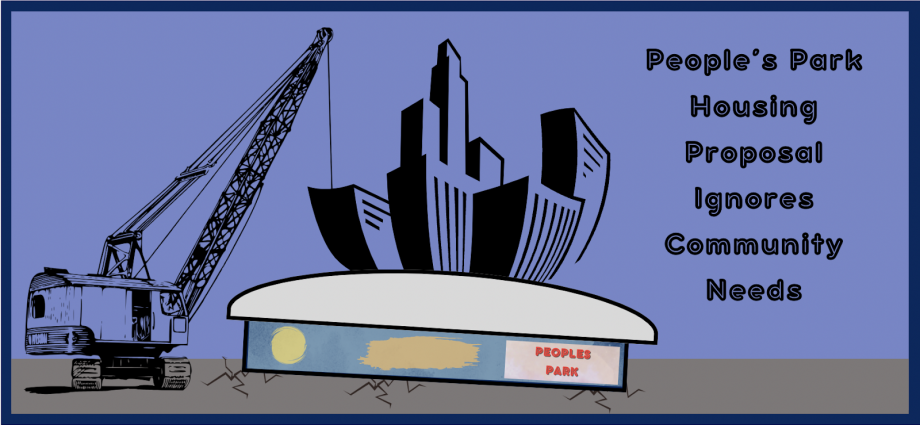

The BRB Bottomline: As the price of housing soars, UC Berkeley’s plan to build units in People’s Park is sparking backlash from members of the community.

Berkeley’s housing situation is a defining challenge for the city, reflective of larger problems in the state of California. Local housing is both scarce and expensive due to restrictive government regulations and vocal opposition from locals, squeezing students and other renters. This dangerous combination, in addition to an inadequate social safety net, has resulted in about a thousand homeless people living in Berkeley.

However, it appears that help is on the way. A new bill to advance the proposal to build new housing in People’s Park was signed last month by California Governor Gavin Newsom. The bill, AB 1307, changed California’s regulations on building construction so universities no longer have to consider the noise pollution created by students living in the newly occupied housing. AB 1307 eliminates what was one of the strongest legal obstacles to the progress of the People’s Park project, moving plans forward. The planned development would convert a third of the park into housing for 1,100 undergraduate students and 100 currently unhoused people, according to a statement issued by the university.

The Economic Angle

University administration created this measure to address U.C. Berkeley’s severe housing shortage. Right now, the university only houses 22% of undergraduate and 9% of graduate students, providing only about 10,000 beds for 45,000 students.

Basic economic principles indicate that when demand for a good or service is much greater than supply, intense consumer competition will cause the good to be both expensive and difficult to acquire. Over the past few decades, the university, much like the rest of California, has been unable to keep up with the growing demand for housing, which economically harmed both students and Berkeley residents. Every U.C. is facing some version of this problem. Overall, 5% of students in the U.C. system do not have stable places to sleep. Furthermore, factors like universities’ reluctance to spend on expensive building costs and frequent environmental lawsuits against construction have blocked or delayed many pipeline projects.

From an economic standpoint, the solution to this problem is very simple — just increase the supply of housing. In theory, when a municipality does this, the price of housing decreases, making housing easier to find and more accessible to historically excluded working-class and minority families. However, implementing this solution is arduous in places like California, where new housing is difficult to build.

The People’s Park project is a sound solution from a purely economic perspective. However, economic issues never exist in a vacuum, especially on a community level. The university’s lack of consideration for the social and cultural significance of the park will only hurt those who need housing the most. Although the park is by no means an ideal place for people to live, it has been home to unhoused people for decades. Although the university has provided temporary housing options, current park residents may be reluctant to leave a place they see as their home, especially if they feel forced out.

Needlessly Stoking Controversy

Although attempts to resolve Berkeley’s housing crisis should be applauded, this particular proposal is incomplete and imperfect. Local activists have criticized the plan because it will displace the unhoused population living in People’s Park without promising them a stable home in the long term. This approach does not solve the problem — it just moves the unhoused from one place to another.

Furthermore, there are more general concerns about the project’s impact on Berkeley’s cultural landscape, given the history preserved in People’s Park. The park was founded in 1969 on unused land owned by the university. Community members planted a garden and built a playground there, and it became a site for many protests and confrontations with law enforcement. In the 1970s, People’s Park became a hub for unhoused people in Berkeley. Throughout the park’s history, the university’s previous attempts to build on it have failed due to local opposition.

In an interview, Chancellor Carol Christ said People’s Park, as the largest prospective site for new housing, was “essential” for the university’s efforts to build more student housing. If People’s Park is the only site usable for such a project, U.C. Berkeley’s stubbornness would be understandable. However, there are up to 15 feasible alternative locations that the university has refused to even consider. It’s highly unlikely that any of these sites would have sparked the same firestorm as they do not have the unhoused presence or cultural significance of People’s Park.

In short, support for the development is a matter of priorities. The university seems to want to build housing at the site as quickly as possible, even if there are short-term consequences. Nevertheless, the wishes of the unhoused population and community members must come first. UC Berkeley should not destroy a core part of the city to build housing that could be built elsewhere.

Take-Home Points

- Gov. Newsom recently signed a bill, AB 1307, that allowed the People’s Park project to bypass the environmental regulations that were blocking it.

- Economically, the project attempts to address Berkeley’s housing shortage by increasing supply, which should lower the cost of rent in the area.

- The project has been criticized for displacing the local unhoused population and destroying part of Berkeley’s history and culture.

- The university also neglected to consider alternative housing sites, which could have provoked less backlash from the community.