Author: Regina Wang, Graphics: Dennis Mach

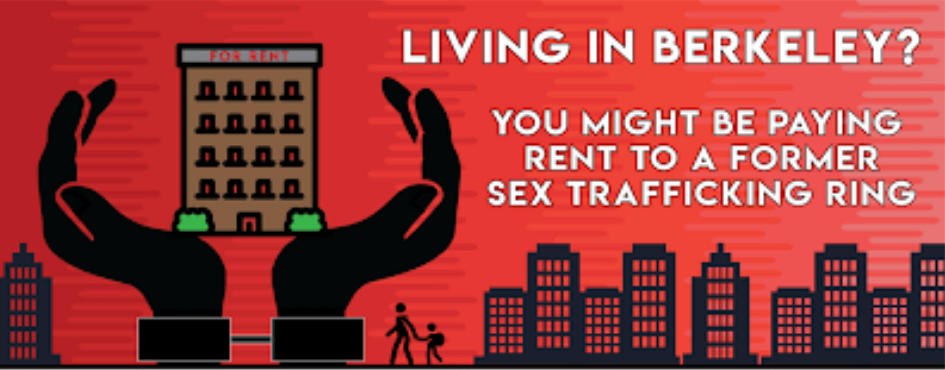

BRB Bottomline: The United States Attorney’s Office of the Northern District of California introduced the Lakireddy Bali Reddy case to the public twenty years ago. A real estate tycoon with over 1,000 properties in Berkeley and surrounding areas was guilty of sex trafficking and immigration fraud. However, his and his family’s real estate businesses, Everest Properties and Raj Properties, continue to operate in the Bay Area to this day. How are these businesses still operating, and how has this incident shaped the Berkeley community?

In late 1999, Berkeley High’s school newspaper, the Berkeley High Jacket, received a tip from a teacher. Indentured servitude could have been at play in the recent death of Chanti Prattipati, 16. She passed away due to carbon monoxide poisoning on November 24, 1999 in an apartment in Berkeley. The coroner had ruled it a death by accidental carbon monoxide poisoning, and police did not investigate further.

Megan Greenwell, a staff writer, and Iliana Montauk, a news editor, found something questionable: though the girl was sixteen years old and lived in Berkeley, she was not enrolled at Berkeley High. Eventually, they published a report titled “Young Indian Immigrant Dies in Berkeley Apartment” with the subheading, “South Asian Community Says ‘Indentured Servitude’ May Be to Blame.” They reported that the deceased teen may have been an indentured servant brought over from India by Vijay Lakireddy, the son of Lakireddy Bali Reddy, 62, a wealthy and powerful local landlord.

Then the two students went on winter break and forgot about the article.

This case was about much more than indentured servitude. In mid-January of 2000, Lakireddy Bali Reddy and his son were charged by federal prosecutors for smuggling Indian women into the U.S. for illegal sexual activity, conspiracy to commit immigration fraud, and false statements on a tax report. Prosecutors claim that Reddy took advantage of casteism and economic class to exploit these women and used his business holdings to help him do so. The San Francisco Public Press reported that he owned over 1,000 units in rental properties in the Bay, generating upwards of a million dollars a month in rental payments. He was the biggest landlord in Berkeley, second only to the University of California.

Lakireddy Bali Reddy

Lakireddy Bali Reddy left India in the 1960s to study chemical engineering at UC Berkeley. After opening Pasand Madras Indian Cuisine in downtown Berkeley in 1975, he used the restaurant’s income to buy up real estate properties in the city. As he accrued wealth and holdings, Reddy sent money back to his home village of Velvadam in southern India. His contributions and ties to America lent him much influence in Velvadam, and in 1986, he began bringing people from his small, impoverished village in the state of Andhra Pradesh over to America to work in his businesses.

The young girls that Reddy brought over were members of the dalit, or “untouchable” caste. Dalits are historically on the lowest rung of the caste system, being considered “unclean” and generally only able to work in the most distasteful professions. Though India officially abolished the caste system in 1950, it remains omnipresent in many Indians’ day-to-day life and continues to be a large source of discrimination.

In this small village of 7,000, Reddy was essentially a lord. He would buy young girls of the “untouchable” caste from their parents, having them first work in his Velvadam estate and eventually export them to work in his Berkeley businesses. This is the path that brought Chanti Prattipati and her 15-year-old sister, who had been discovered at the same time but survived, to Berkeley.

The indentured servants worked at Reddy’s businesses and apartment buildings for little more than food and board. They were subject to rape and abuse. As Assistant U.S. Attorney John Kennedy said in court papers, Reddy was “unimaginably wealthy, all-powerful, and in apparent full control of the world in which they were brought to live.”

In 2001, Lakireddy Bali Reddy was convicted on two counts of transportation of minors for illegal sexual activity, as well as conspiracy to commit immigration fraud and filing a false tax return. The Justice Department found that Reddy had been “carrying out a widespread conspiracy since 1986” to bring between 25 and 99 Indian laborers into the United States through false pretenses, subjecting them to “sexual servitude.” The sexual abuse, coupled with the effects of cultural and physical isolation and the “extreme duration of Reddy’s sexual exploitation,” caused the victims to undergo extreme psychological injury.

Though the original plea deal that prosecutors reported had a maximum sentence of 38 years, Reddy’s lawyers bargained it down to 8 years. Reddy also paid $2 million in restitution fees, and four of his family members pleaded guilty to lesser charges. After a class-action civil lawsuit was brought against Reddy in 2002, he paid an additional $8.9 million to other victims.

Two Decades Later: Continued Presence in Berkeley

So, what has happened since then?

According to Women Against Sexual Slavery (WASS), after finishing his sentence in prison, Reddy moved into a newly built mansion in the Berkeley Hills. The LA Times reported that he returns to his home village two times a year, where he remains a prominent and respected figure. Reddy Realty, one of his real estate management companies, has closed since the case came out. His restaurant, Pasand Madras Indian Cuisine, has closed too, after widespread boycotting and protest in response to the case; picketing, organized by Marcia Poole and Diana Russell of WASS, had driven customers away by spreading awareness of his crimes and his family’s connection to them.

According to an article written by the Daily Cal, as of 2013, Reddy still owned Everest Properties and received income from the estimated over 1,000 rental properties. And as of 2017, members of his family still owned Raj Properties, another large real estate management company in Berkeley.

The continued survival of these companies linked to Reddy and his family may be because of the lack of institutional memory and high demand for student housing. Unlike the constant picketing at Pasand Madras in the past, there is no public protest against Raj or Everest Properties today.

In an interview with Greenwell, one of the original Berkeley High reporters, she stated that while the case is “very much something that Berkeley [city] residents remember and talk about,” it may be different for students at UC Berkeley. “It makes sense that students at Cal wouldn’t know much about the Reddy case. [Reddy]’s primary customer base cycles out within every four years.” Unaware students may sign with Everest or Raj Properties without qualms, allowing for the companies’ continued success.

An undergraduate student at UC Berkeley who recently signed a lease with Raj Properties has a different perspective on why these real estate companies continue to attract business.

“My roommates and I, to the surprise of many, were aware of the Reddy case when we made our final housing decision,” she said. “Initially, we all were immensely turned off by this company and all agreed to not rent any apartment that was owned through the companies of this family.”

She went on, however, to detail issues that came up when she and her roommates were searching for housing, including roommate changes and the “competitive nature of and lack of relatively decently priced apartments that provided decent square feet, distance from campus, and living standards.” Eventually, they found one that was perfect according to all their criteria except for one. It was owned by Raj Properties.

While “the fact that this apartment was owned by Raj Properties was definitely still at the back of our heads and still very unsettling, [the] competitive nature of decent off-campus housing options drove us to prioritize merely securing an apartment. Still to this day, I would prefer to not sign a lease with Raj Properties due to the sexual trafficking (and other criminal) history within the family company owners, but constricting circumstances led us to.”

When asked about the level of knowledge regarding this case in the student body at Cal, the student stated that while she does not believe the Reddy case is “widely known,” it is “definitely not a hidden fact.” The ease of finding mentions of the case when Googling Raj or Everest Properties allows for students to learn about the case when researching apartments.

For this student, the history of Raj Properties was definitely an issue in the decision to do business with the company. However, the lack of viable housing options forced her to overlook her moral qualms and settle with the best option she had. In this way, the continued success of Raj and Everest Properties is likely a result, not simply of student unawareness, but of a much more systemic issue: the saturated and competitive housing market in Berkeley and the broader Bay Area.

Effects on Legislation and the Berkeley Community

The Lakireddy Bali Reddy case has had a multitude of effects outside the housing market as well.

As reported by the San Francisco Public Press, the case started a statewide conversation “that led directly to the passage in 2005 of Assembly Bill 22, California’s first law setting higher criminal penalties for human trafficking.”

That 2005 law provided a stepping stone for much stricter provisions against sex trafficking. In 2012, The Californians Against Sexual Exploitation Act, also known as Proposition 35, was passed with 81% approval, making it the most popular initiative in California history. The law included provisions for law enforcement training in sex trafficking, which could have given police the tools necessary to detect the 14-year-long Reddy sex trafficking ring sooner, according to Michael Rubin, the attorney in charge of the 2002 civil case against Reddy.

For Anirvan Chatterjee, co-curator of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour, the Reddy case “shook [his] faith in the Indian-American community.”

“Growing up, I had a sense of safety and community in the Indian-American community, but the case was the first time learning that you can’t trust everyone … It cut into our sense of community, cut into our sense of trust.” He stated that there was a divide in the community between the people who stood up for trafficked workers and those who stood behind the landlord, and Chatterjee remembered wondering, “Which side are we going to take?”

“[The case] was definitely a catalyst for South Asian organizing and creating change.” The activism work related to the Reddy case, including working to provide translators and attending court hearings, “helped to prepare South Asian communities to respond to hate attacks and discrimination that arose after 9/11.”

In a similar vein, the Alliance of South Asians Taking Action, a volunteer group in the Bay, was formed in direct response to the Reddy case. To this day, it works to educate, support, and empower South Asian communities in the Bay Area, hosting workshops, resource fairs, and marches on a number of platforms.

As for those two Berkeley High students who broke the story before anyone else did?

Montauk is now a product manager at Upwork and previously co-founded Gaza Sky Geeks, a start-up incubator. She has also worked as a life coach, among other pursuits. Montauk says the case probably affected the college she attended, having written about cracking the case in her college essays. On the Reddy case, Montauk stated, “I personally would never rent from him.”

Greenwell, her colleague, says, “The case definitely shaped my future career path in journalism.” She is currently the editor-in-chief of Deadspin and has worked at the Washington Post, Esquire, and ESPN. A big part of her life, she says, is mentoring high school and college students in journalism. “Even if [they’re] not a professional, that doesn’t mean that they don’t have something important to write about.”

Take Home Points

The Lakireddy Bali Reddy case remains an indelible mark on Berkeley’s history, one which extends to the current day, one which is partially obscured by a severe student housing crisis and lack of institutional memory. Though common knowledge among longtime city residents, the case may come as a surprise to students at UC Berkeley, some of whom may find the question of whether or not to rent a difficult one. Weighing moral considerations against other criteria is a problem each of us will inevitably face. The key, when challenged by such a dilemma, is to be educated about each situation. In the decision-making process, after all, understanding the issue is the first step—and, perhaps, the most important one.

Correction: A previous version of the article stated that Megan Greenwell previously worked at the Wall Street Journal.

But a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw outstanding

layout.