Author: Andrés Larios, Graphics: Caroline Yee

The BRB Bottomline

In the past few decades, the digital revolution has completely changed the way we live. How has it changed the way we work?

With the rise of self-sufficient capital’s consumption, firms are becoming increasingly efficient and productive while the average worker is not seeing these gains. In this transitionary period, laborers are being displaced, while productivity continues to increase. This article discusses the dirty side of the digital revolution and how it has negatively impacted workers.

A Transitionary Period

The digital revolution has undoubtedly changed our world. By using new technologies in every facet of our daily lives, it is easy to see how we use our leisure differently as we engage in video games, social media, and digital art. These byproducts of the digital revolution have undoubtedly changed our habits, but how have they changed our labor systems?

Economists had predicted that as innovation and productivity increased, people would work less and have easier lives. Though the digital revolution is well underway, the daily routines of workers haven’t changed with the times. Most people still work a nine to five, while many work multiple jobs. Life in the digital age has become more competitive and apathetic. Although automation helps us perform difficult tasks more efficiently, workers are being displaced and are told to be re-educated to return to the job market, only to earn less. These are the costs of this transitionary period and the reasons why policymakers must prioritize workers.

Utility of Labor vs. Capital Today

With worker displacement being a prevalent problem in today’s world, how can we explain productivity in the United States increasing linearly since 1950? In a nutshell, capital is becoming more productive. Computers, machinery and new technology make us more efficient and have now become an extension of the average worker, generating higher output in less time. Yet, firms continue to demand the same hours and commitment for the same real wage.

Firms are buyers in the labor and capital markets as these two inputs help them produce outputs. Whereas firms look to maximize production using the most profitable combination of labor and capital, capital is now overutilized compared to labor with this trend accelerating, especially for low-skilled laborers. As capital continues to become more efficient through automation, algorithmic decision making, and general accessibility, a firm’s productivity will too. This has led to firms investing more in capital than in labor.

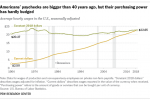

While union membership has fallen dramatically, workers have new tools at their disposal which allow productivity rates to continue to trend linearly. However, because the return on capital is becoming greater than the return on human labor, compensation does not increase at the same rate anymore. As the chart above shows, productivity and worker compensation used to trend upwards at similar rates. With the fall of union membership and the rise of self-sufficient capital, worker representation in labor practices and policies declined tremendously.

In terms of real wage, we can clearly see workers’s purchasing power staying relatively constant since the 1960s. While real wages are currently at a record high, they are still at the same value as wages in the mid-1970s. This fact communicates how ever since the rise of automation and the peak of Union impact, laborers have not received their fair share of payment. The demand for labor will continue to fall in capital-investment heavy industries, leading to continued stagnation in wage and compensation.

Outdated Underemployment Metrics and Automation

Nowadays, workers are being displaced in the name of efficiency. If certain jobs can be substituted by capital, those workers will be abandoned by firms. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, displaced workers are more likely to earn less in their new jobs than their old jobs, especially if they are older. In theory, this should be an indicator of underemployment in the country, however, the data states that this rate has decreased by 10% since the Great Recession.

In a publication by David Blanchflower and David Bell, they argue how the current underemployment rate measurements are outdated as part-time workers who want full-time jobs do not capture the full picture. In a world that is creating new positions, while abolishing the old, many people are finding new full-time jobs that they are simply overqualified for because of shrinking markets and the need for income. These considerations are being ignored by current measurements, completely masking the problem that self-sufficient capital is creating for laborers.

With industry’s current valuation of capital and their ability to produce large amounts of output without considerable pushback from labor unions, productivity rates will continue to rise. Automation has allowed the production and consumption of goods and services to skyrocket, but the cost on the labor market remains unseen. This, coupled with outdated underemployment metrics is completely shielding policymakers and economists from this ever-growing problem which can only get worse.

Take-Home Points

- The labor market’s composition has changed incredibly since the beginning of the digital revolution

- Productivity rates in the United States have increased, despite the displacement of low-skilled workers through automation

- Worker compensation has decreased since the 1970s with the rise of self-sufficient capital and declining union participation

- With misleading underemployment rates and increasing productivity, this labor crisis is largely invisible