Author: Bradley Tian, Graphics: Nina Tagliabue

The BRB Bottomline

The COVID-19 has, unequivocally, triggered a global crisis comparable in size to historical precedents such as the Great Recession of 2008. While the two may be similar in their ramifications, the current crisis differs significantly from the 2008 crisis, revealing noteworthy insights for policymakers and investors alike.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 and the current one instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic have each claimed their respective titles as the largest global recession since the Great Depression. While both have inflicted significant contractions and volatility in financial markets worldwide, the two crises have notable differences in both their origins and their process of manifestation; the former was a financial crisis kindled by internal collapses of banking systems, while the latter is a global standstill induced by prevailing health threats. This article will focus on reviewing the progression of the 2008 GFC, as well as exploring key differences between the 2008 GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Understanding the 2007-2008 Global Financial Crisis

In 2001, the US economy underwent a periodic recession caused primarily by terrorist attacks, the dot-com crash, and massive accounting scandals. The federal government responded by reducing interest rates numerous times, which prompted the proliferation of cheap loans and credit. This influx of liquidity appealed to high-risk investors and desperate borrowers, especially those without income, jobs, or assets. As a result, the housing market flourished with subprime (low-credit) mortgages being distributed restlessly. Massive inflation in real estate prices followed suit. Furthermore, banks began to seek profit by distributing collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) to financial institutions. Essentially, these packages used the assets of borrowers (real estates, mostly) as collaterals, redirecting loan payments to contracted investors. The development of subprime loans drove exponential growth in the financial market – a bubble that began to burst in 2007.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis began with subprime borrowers nationwide defaulting on their mortgages due to increased interest rates and saturations within the real estate sector. Financial institutions, overwhelmed with collateralized assets, faced significant liquidity problems. Consequently, market confidence plummeted sharply, and many financial institutions began filing for bankruptcy. Grave concerns arose all across the nation since bankruptcy within the financial market will result directly in the halting of all business activities. The federal government intervened heavily, providing bailouts and slashing interest rates to as low as 1%. It eventually enacted the National Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, releasing $700 billion to cover distressed assets.

As explained above, a prominent driver of the 2008 GFC is the lack of regulation on financial derivatives and credit policies. The crisis called for greater caution regarding high-risk financial instruments and scrutiny over mortgage distributions. While economic and financial damage generated by the COVID-19 pandemic is comparable to the result of the 2008 GFC, the current crisis has a vastly different origin and calls for different approaches for an eventual recovery.

Comparing the 2008 GFC with the COVID-19 Pandemic

While the two crises are vastly different in their origins and progression, both the 2008 GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic are similar in igniting global uncertainties and massive economic contraction. Back in 2007, a lack of scrutiny on financial instruments and asset transactions resulted in skyrocketing uncertainties regarding the magnitude and severity of the underlying risks. This resulted in the freezing of international financial relationships, as well as increased volatilities in the forex market. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic also caused a spike in global uncertainty with the suspension of international business activities, stagnation in global supply chains, challenges in healthcare systems, dilemmas in governmental intervention, survival of physical retails & services, exacerbation of socioeconomic inequalities, and other dire concerns regarding the economic, financial, and political landscape.

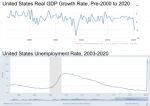

Another significant factor is the impediments to economic prosperity. Both crises negatively impacted the US Gross Domestic Product and unemployment rates (see chart below). In its latest World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Foundation (IMF) predicted that the global growth rate will decrease by 4.9% in 2020, which is particularly alarming for the lower class as the impediments may erase progress towards poverty reduction since the 1990s.

Nonetheless, the 2008 GFC and the COVID-19 Pandemic are more different than they are similar. Below are the key factors distinguishing today’s crisis from the past.

Supply and Demand Shocks

The financial crisis of 2008 began with the paralyzation of demands in the real sectors – a combination of falling housing prices, subprime mortgage collapse, and overall decreased consumer spending – which then led to severe liquidity stagnation in the financial market. In 2020, however, the supply shocks came first due to the widespread lockdown in effect. In order to limit the spread of contagions, supply chain maintenance has been halted worldwide; for instance, the closure of Chinese factories have led to a lack of components for US firms. Furthermore, this sudden stagnation of supplies was followed by a shock in demand in the form of increased price sensitivity and a lack of customer activity. In regards to supply and demand, the two crises generated negative economic impacts through opposite directions.

Enforced Regulations for Banks

Banks were the epicenter of disaster during the 2008 GFC. Their general underestimation of risks within subprime mortgages contributed to the growing bubble in the housing market. During COVID-19, however, the economic downslide was because of the lockdown implemented to limit the outbreak. Today, the banking industry aims to serve as a buffer for the suffering population. Major banking institutions such as J.P.Morgan and Bank of America aim to collaborate with their rivals to establish support for struggling companies, and industry leaders have pledged to cancel stock buybacks in order to remove the industry’s stigma of selfishly profiting during times of crisis. In addition, enforced regulations such as the Dodd-Frank Act require banks to prepare a more durable financial cushion. The level of uncertainty may be similar for the two crises, but banks are better equipped to retaliate against a financial disaster this time.

Governmental Reactions

The federal reserve has become increasingly supportive of private businesses in the current crisis than before. In 2008, the federal government refused to provide sufficient aid to Lehman Brothers, leading to the collapse of the 158-year-old investment bank. Today, the federal reserve has responded boldly to the COVID-19 by reducing interest rates to 0% and purchasing corporate bonds from distressed companies. In addition, stimulus packages further expressed the government’s stance to prevent severe recessions. Although these rapid measures of quantitative easing have been effective in the short term, overuse of federal assistance can result in long-term liquidity problems.

Take-Home Points

The differing qualities of the 2008 GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that historical phenomena may overlap, but they never fully repeat. This exploration of the drivers and implications of the two crises calls for both policymakers and opportunity-seeking investors to remember historical progressions and developmental models but also remain keen and adaptive to changes exclusive to the current situation. The progression of today’s crisis will depend on the recovery process targeted at the COVID-19 pandemic and the speed at which countries worldwide would return to economic normality.