Conflict in Ukraine is Pushing Food Supplies to the Brink

Author: Sean O’Connell

The BRB Bottomline

The Ukraine conflict represents an existential threat to global food security as some of the world’s largest food exporters: Russia and Ukraine, become embroiled in war. Low-income countries are particularly exposed, with potentially major geopolitical and humanitarian implications.

As the war in Ukraine enters its second month, the West is experiencing these spillovers as daily annoyances: rising prices at the gas pump and higher transit costs. But for many developing countries, the conflict threatens to destabilize global food supply chains in ways that could yield disastrous results.

Europe’s Breadbasket

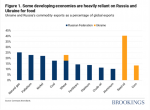

Russia and Ukraine are the world’s first and fifth largest wheat exporters, respectively. Ukraine is also the largest sunflower oil exporter and the third largest corn supplier, as shown in Figure 1 below. According to the New York Times, between 2017 and 2022 the two countries “accounted for nearly 30% of the exports of the world’s wheat, 17% of corn, and 75% of sunflower seed oil.”

A major reason for such high productivity is geography. Ukraine and West Russia occupy a historically fertile part of Western Eurasia known as “Europe’s breadbasket.” The rich, black soil known as Chernozem brought war to Ukraine long before Putin’s aspirations to “historic Russia” existed. Hitler’s lebensraum demanded massacring and enslaving Ukrainians so that ethnic German farmers could take advantage of the region’s prodigious geography. And Stalin’s disastrous collectivization efforts singled out Ukrainian peasants as malicious kulak enemies—leading to the starvation of 3.5 million Ukrainians during the Great Famine of 1932.

However, while the Great Famine may help explain socio-cultural elements of the current conflict, it’s the rest of the world, not Ukraine, that risks food shortages as a side effect of war. In a good year, grain yields in Russia and Ukraine can be extraordinarily high. Late last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture predicted Ukrainian wheat yields for 2021-2022 to reach 31.2 million tons, with corn yields at 39.1 million tons. While the same report anticipated a 9% decline in Russian wheat production, 118 million tons of grain were expected to be marketable this year. Russia and Ukraine combined, mainly through their wheat and corn outputs, account for 12% of worldwide calories consumed.

The principal importers of Russo-Ukrainian grains are concentrated in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Africa. According to an analysis by The Breakthrough Institute, a climate change think tank, “12 countries rely on a combination of Russian and Ukrainian wheat for over 50% of their total wheat supply, 22 for more than 40% and 32 for over 30%.” The largest wheat importers are Egypt, Turkey, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, though several smaller countries have found themselves dangerously overexposed to the conflict’s trade disruptions. Specific country data is shown above in Figures 2 and 3 from the Financial Times.

Many of these countries are in regions already hard hit by geopolitical instability and climate change. Lebanon, for example, imports 70% of its grain from Ukraine and is in the midst of a migrant crisis, monetary devaluation, and growing sectarian violence. Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, purchases about 80% of its overseas wheat from Russia and Ukraine. Imported wheat makes up about two-thirds of Egyptian consumption. Other high exposure countries include Tanzania, Oman, and Nicaragua, which “import more than 60% of their total wheat supply from a combination of Russia and Ukraine.” Based on UN Commission on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) data, Sub-Saharan Africa has particularly high reliance on the two countries’ imports: 62% in the Republic of the Congo and almost 100% in Benin and Somalia.

The world’s poorest countries are therefore among the most Russo-Ukrainian saturated importers. In total, the “least developed countries” as defined by the United Nations, averaged 40% of their wheat import intake from the two countries in 2008-2020. As a result, a UNCTAD report states that 5% of the import basket from the world’s poorest nations are likely to be affected by the Ukraine conflict, as compared with less than 1% for richer states.

The War on Wheat

The pace and destruction of the Russo-Ukrainian War quickly dashed hopes that the globe’s grain suppliers could keep pace with demand. Ukrainian President Zelensky has been quick to put the country’s economy on a war footing, which includes prioritizing fuel and manpower to the military and suspending Black Sea port export activity. In Mid-March, the country’s Ministry of Agriculture announced, according to NBC News, a ban on the export of food staples to “meet the needs of the population in critical food products.”

Russian cereal exports have been similarly stunted. Financial sanctions are crippling export and investment capabilities for most companies. President Putin recently banned grain exports abroad in a move calculated to make the international community feel the pinch of condemning Russian expansionism. In sum, the World Food Programme (WFP) claims 16 million tons of corn and 13.5 million tons of wheat remain un-exportable from the two countries. This represents a shocking 43 and 23% of total expected country exports for the 2021-2022 cycle.

Prices have responded accordingly. An article in Radio Free Europe reported that the first month of Russia’s invasion saw wheat prices rise 21%, with other grains like barley facing 33% rises.

Unfortunately, offsetting these price rises by increasing production in other countries will come with additional expenses. U.S. and EU sanctions on Russian energy exports—including natural gas—have deeply affected the fertilizer industry. Prices rose 43% for key nitrogen-based fertilizer inputs for grain cultivation. Professor of Agricultural Economics Mark Welch described the hike as energy-dependent: “About 75% of producing these fertilizers is actually the cost of natural gas.” Fertilizer was already abnormally costly before the war, and now is estimated to be three-to-four times as expensive as in 2020.

The conflict’s resource drain and physical damage also means future Ukrainian cereal yields will likely be dismal. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) reports that only one-fifth of Ukraine’s large agribusinesses in mid-March had the fuel supplies needed for regular spring planting. The Agriculture Ministry also announced that the war “”risks creating a 30% reduction in cultivated areas,” with some estimates as high as 50%. President Zelensky put it another way: “Our country has enough food. But the lack of exports from Ukraine will hit a number of populations in the Islamic world, in Latin America and in other parts of the planet.”

“Catastrophe on Catastrophe”

The state of global food supply wasn’t rosy even before the Russo-Ukrainian War began. As the Executive Director of the WFP David Beasley noted, “Ukraine has only compounded a catastrophe on top of a catastrophe. There is no precedent even close to this since World War II.” Climate change and coronavirus have together been responsible for precipitous rises in worldwide food prices and in recent years. According to the United Nations, between 720 and 811 million people faced hunger. A 17.9% increase in global undernourishment and the 320 million new food insecure individuals created in 2020 were largely attributed to pandemic disruptions.

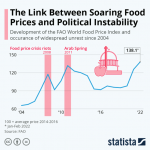

The pandemic also reduced worldwide GDP growth as well as human and infrastructure capital investments. The result in many regions has been productivity declines and the breakdown of global supply chains, often increasing the pre-pandemic costs of goods. Wheat is no exception, and international prices rose 69% in 2021 alone. As Figure 4 shows below, although 2020 saw precipitous declines in fertilizer and fuel price indices—due to reduced demand—food costs continued to rise until they matched the 2008 “crisis” levels that triggered price riots throughout the developing world, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute. Since 2019, global cereal prices have grown 48% and fuel prices a shocking 86%.

The dual pressures of high prices and reduced income due to the pandemic (The World Bank believes nearly 97 million people may have been forced below the international poverty line in 2020), are a worrying harbinger for developing nations. Food prices can make or break livelihoods in poorer countries, where nutritional expenditures often constitute 45% or more of a household budget. Similar cereal price spikes in 2007-2008 and 2011-2012 (shown in Figure 4) are estimated by World Bank researchers to have resulted in 155 million and 44 million individuals pushed into poverty, respectively.

Yet, the bad news keeps coming. Climate change is again rearing its ugly head for the 2022 harvest season. China recently rang alarm bells in anticipation of the country’s “worst seedling situation in history,” according to its Minister of Agriculture. The New York Times reported that China had been unable to plant one-third of the crop on time last year, dampening prospects for this year’s harvest. The delay was due to unseasonably severe flooding patterns in Henan Province last year that were attributed to climate change.

This doesn’t bode well for the many smaller developing countries who are already competing for limited exports in the wake of the Ukraine conflict. China is the world’s fourth largest wheat importer, meaning its 9.5 million metric ton purchase last year will likely need expansion to offset a floundering domestic crop yield. Unless this demand can be offset by hoped for bumper crops in countries like India, the global cereal market may become highly politicized.

An Arm and a Leg, Literally?

But what do high grain prices really mean for the people and countries affected? An estimate by the Center of Global Development estimates that at least 40 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty because of the 2022 price spike. The United Nations provides a more conservative, but nonetheless disturbing, prediction that 7.6 to 13.1 million people could go hungry as a direct result of the war in Ukraine. As the report explains, the combined effect of war, broken supply chains, and climate change could parallel “a proverbial man being already so far submerged in water ‘that even a ripple is sufficient to drown him.’”

On the ground in affected countries, the situation looks equally grim. Take Egypt as a case study. The country’s reliance on wheat imports to subsidize the population’s staple eish baladi flatbread means that nearly 12.3 million tons of overseas wheat were needed in 2021. However, with prices skyrocketing from $271 per ton in late 2021 to $389 in March, Egypt will likely have to substantially increase its already $3.3 billion dollar bread subsidy that helps feed 88% of the population.

Egypt is no stranger to political instability stemming from high food prices. Bread riots in 1975 and 1977 against the Sadat Government resulted in hundreds of deaths. And unrest surrounding the 2008 food price hikes gave Mubarak’s government a taste of what was to come in the 2011 Arab Spring—also triggered by rising food costs. Cairo seems acutely aware of this history. The government has already banned home-grown wheat exports and capped unsubsidized bread prices in anticipation of unrest. Further, as Figure 5 below shows, the relationship between food prices and unrest is far from unique to Egypt.

In other countries the war’s price effects are already impacting domestic politics. On March 9 Al Jazeera reported protests in the Iraqi city of Nazriya over high food prices from the Ukraine conflict. One protestor stated, “The rise in prices is strangling us, whether it is bread or other food products.” The Lebanese Central Bank, which subsidizes private wheat imports, stated it “has no capacity to pay higher [grain] prices.” In Libya, the Ministry of Economy is also already struggling to manage limited cereal reserves and stall flour supply crises in several cities.

For the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), an organization that buys food on the open market to provide it to nutritionally insecure countries and people, the situation is similarly tight. In particular, the organization provides approximately 13 million Yemenis with emergency food access—over a third of the population in a country ravaged by political crisis and famine. Yemen is almost completely reliant on food imports and heavily dependent on WFP assistance.

Yet, according to the WFP’s Executive Director David Beasley, the organization may soon need to make the decision to “take food from the hungry to give it to the starving.” The Breakthrough Institute reports the organization previously used Ukraine for about half of its grain purchases. As a result of heavy supply reliance, coronavirus, and climate change, Politico reports the WFP now faces an $8 billion dollar shortfall that can’t be covered by current budgeting.

Add this on top of three million food insecure Ukrainian refugees, and the WFP may struggle to continue delivering “more than 4 million tons of food to over 100 million people each year.” Beasley paints a starker picture: “Failure to provide this year a few extra billion dollars means you’re going to have famine, destabilization, and mass migration.”

A Way out of the Dark?

With developing countries and international organizations facing such bleak decision-making calculus, policymakers have made several recommendations to ease the impact of the Russo-Ukrainian War on food supplies.

In the short-term, it remains vital that the U.S., EU, and its allies continue a policy of non-interference towards Russian foodstuffs. According to the Center on Global Development, “The G20 and other grain producers must keep markets open and avoid sanctions on food, even if further disruptions arise, to avoid artificially exacerbating the impacts.” Food sanctions would not only be symbolically impolitic but could also cut off what little grain supply trickle remains in Russia. Some, including Afghani importer Nooruddin Zaker Ahmadi, argue that existing sanctions are already more than enough: “The United States thinks it has only sanctioned Russia and its banks. But the United States has sanctioned the whole world.”

Strengthening the World Food Programme presents another appealing “quick fix” option for wealthy countries looking to help. While the United States contributed approximately $3.7 billion of the WFP’s $9.5 billion in 2021, other wealthy OECD nations remain underrepresented. Australia offered a paltry $115 million, France $83 million, and the Netherlands $53 million. With the right overtures, even China’s token $26 million addition could be significantly and proportionally increased to meet the impending crisis. Donations by richer nations today could reap untold benefits in future averted regional conflicts, civil strifes, and migration swells resulting from food insecurity.

If the price hikes and food shortages remain for the long-term, however, countries and donors may need to get creative with their responses. WFP Director David Beasely is taking the lead. His aggressive approach to fundraising has already seen him face-off with billionaires like Elon Musk and decry the WFP’s budget shortage as a “shame on humanity” when there’s “trillions of dollars of wealth washing around planet Earth.”

At the national level, rethinking bread subsidies and strategic grain reserves could help developing countries adapt to a world where climate change could make food price shocks the rule rather than the exception. In fact, an analysis by the Middle East Institute recommends Egypt consider upgrading its subsidy system to a direct, unconditional cash transfer payment. This so-called “helicopter money” would allow the working poor to decide for themselves how to allocate government relief funds towards household consumption.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had global ripple effects as the price of food inputs rise higher and faster than developing countries can keep pace. Without integrated and inventive responses to the challenge of high food prices, the world may face a new era of bread-based political instability and violence. The danger is real: every grade schooler knows that the price of bread can cause revolutions. And the danger is shared. As Beasley counseled, “If you think we’ve got hell on earth now, you just get ready. If we neglect northern Africa, northern Africa’s coming to Europe. If we neglect the Middle East, [the] Middle East is coming to Europe.”

Take-Home Points

- Global food markets face severe shortages and higher prices as two major exporters–Russia and Ukraine–enter a second month of conflict.

- Many developing countries are heavily reliant on grain imports from either Russia or Ukraine, and now risk political instability as a result of the war’s disruptions.

- High food prices were already a problem before the conflict, with the pandemic and climate change seeing reduced yields in some countries and less efficient supply chains.

- Rising price trends, in combination with the war, are pushing international food organizations like the World Food Programme, beyond their ability to assist the world’s most nutritionally vulnerable.

- Responding to the crisis will take policy reshaping as well as immediate relief at both the regional and global levels.