Author: Dheeraj Pesala, Graphics: Erika Hayashida

In a polarizing world, we analyze whether international organizations will stand the test of time. As countries shift to nearshoring and quantitative barriers to trade, the fate of the WTO and its influence hangs in the balance.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) was established in 1995 as the successor to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). It was amended to let in the previously excluded and newly independent socialist bloc, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it transformed GATT from a set of rules to a dynamic intergovernmental organization. The founding countries in the Uruguay Round armed the WTO with the capacity to enforce and define a legal trade framework. Given its commitment to globalization and non-discrimination among its members, the WTO grants all countries equal voting power and makes decisions only through absolute consensus.

All Members Are Equal (But Some Members Are More Equal Than Others)

Oftentimes, the World Trade Organization has fallen short of its commitment to non-discrimination and open borders. While humanity was tested with COVID-19, the WTO could not rise above its differences to take urgent action in expanding access to important healthcare resources. The pandemic exposed deep-rooted inequalities in access to healthcare and pharmaceutical licensing. To overcome this and funnel the developments in fighting this disease, the WTO began to debate a TRIPS waiver.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa during the 1980s and 90s was believed to be exacerbated by the exclusion of the continent from developments in the pharmaceutical sector that could have saved millions of lives. A strong TRIPS agreement and a lack of institutional machinery to overcome the protections granted to pharmaceutical companies prevented poor countries from receiving life-saving medicines. Witnessing this failure, the WTO adopted the Doha Declaration. This allowed member countries to issue compulsory licenses that allowed other countries to freely use patented technology during public health crises. As with all empowering declarations, developed countries soon tried to minimize the scope of its intended effect.

Two decades later, developing countries were quick to utilize the promises of the Doha Declaration at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, most of the developing world wouldn’t see this intellectual property extended to them until late 2022. This was despite robust vaccine technology being created at the beginning of 2021. While nearly one hundred countries rallied for a TRIPS waiver, the G7 countries stalled any consensus. This shift from voluntary cooperation to a prolonged battle of involuntary surrender by developed countries has caused a rift, leading both groups in clear contrast to the Global North’s outward efforts during the mid-20th century. As the world grows weary of technological sabotage, countries have expanded national security to include technological advancements. Given the emphasis on intellectual property, it is very likely that we see decreased knowledge transfer and international cooperation in the future.

The Appeal To Authority Fallacy

Perhaps the most optimistic can rationalize the WTO’s shortcomings and argue that its biggest asset is its dispute resolution mechanism. The concept of an international court passing judgments on countries is based on international collaboration and cooperation. This was particularly strong in the early days; the GATT was created in 1948, which banked on post-war optimism, and the WTO, which made use of the booming economies at the time. In today’s populist and fragmented world, however, cooperation is disincentivized. This line of isolationist thinking has led to the decline of the WTO’s ability to resolve disagreements between countries.

When a member country raises a complaint against another member, they are first allowed to consult each other and mediate an amicable resolution. However, when this fails, the issue is arbitrated by a panel. The judgment of the panel is binding unless appealed by the losing side. The appeals are channeled through the Appellate Body. Recently, it is this widely celebrated mechanism that has been weaponized to stall all progress in judgment delivery at the WTO.

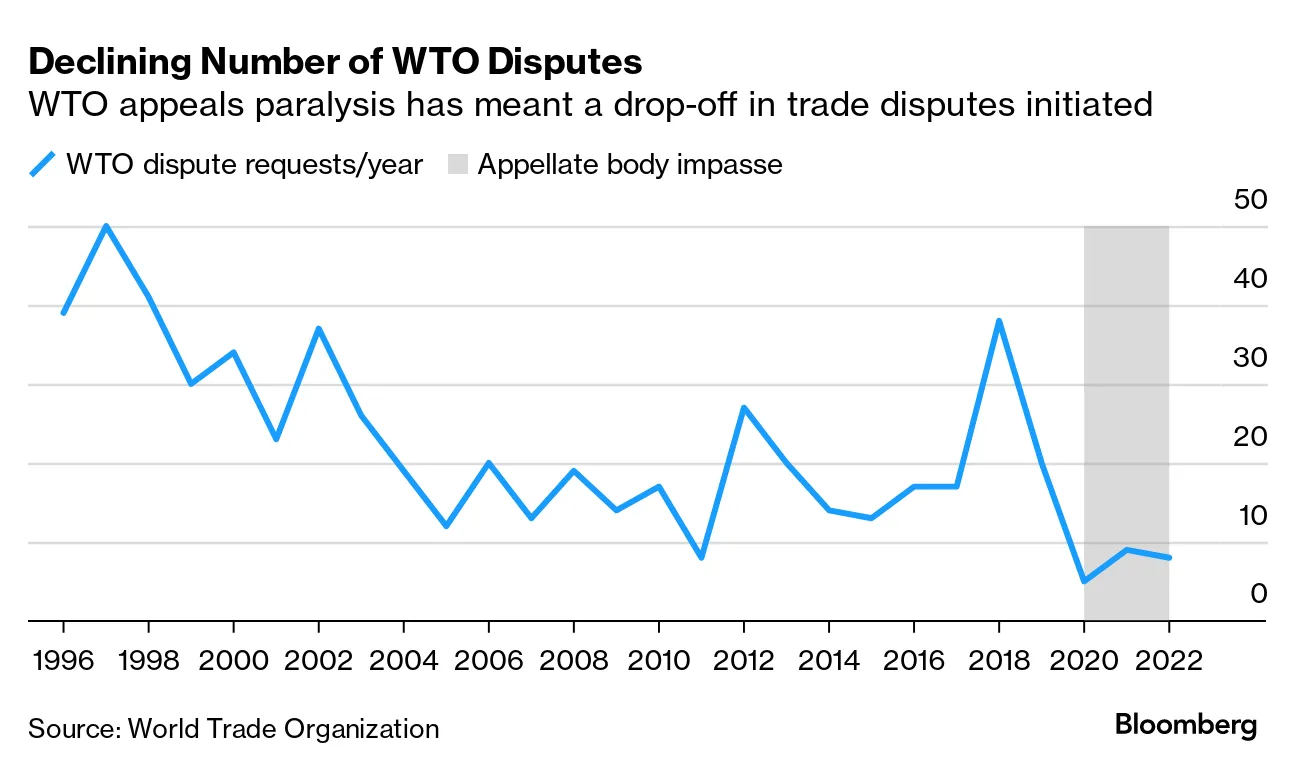

The Appellate Body has been dysfunctional since 2019 because the United States has repeatedly blocked efforts to appoint new judges. It claims that the bench has overreached its purview and has negatively affected its cases. The United States argues that the Body’s non-textualist approach to the application of its rules invalidates the legitimacy of the judgments it renders. It is also dismayed by the judicial activism that the bench sometimes undertakes. Scholars, however, contend that the US has blocked appointments to get away with violating the rules. The tariffs that the Biden administration continued from the first Trump administration, and the extensive industrial subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act, defy trade rules. By “cutting off its legs,” the US ensures that the Appellate Body lets them off scot free.

The way countries make use of this vacuum is through ‘’appeals into the void.’ When there is no Appellate Body to render a final judgment, the decision of the panel doesn’t bind, and the dispute is inconclusive. Despite calls for reforms by various countries and detailed plans of action by the EU and Canada, the US holds steadfast in its decision to block all appointments. By failing to deliver one of its founding principles, one can see through the cracks how the WTO is swayed by one powerful country.

Maker And Destroyer

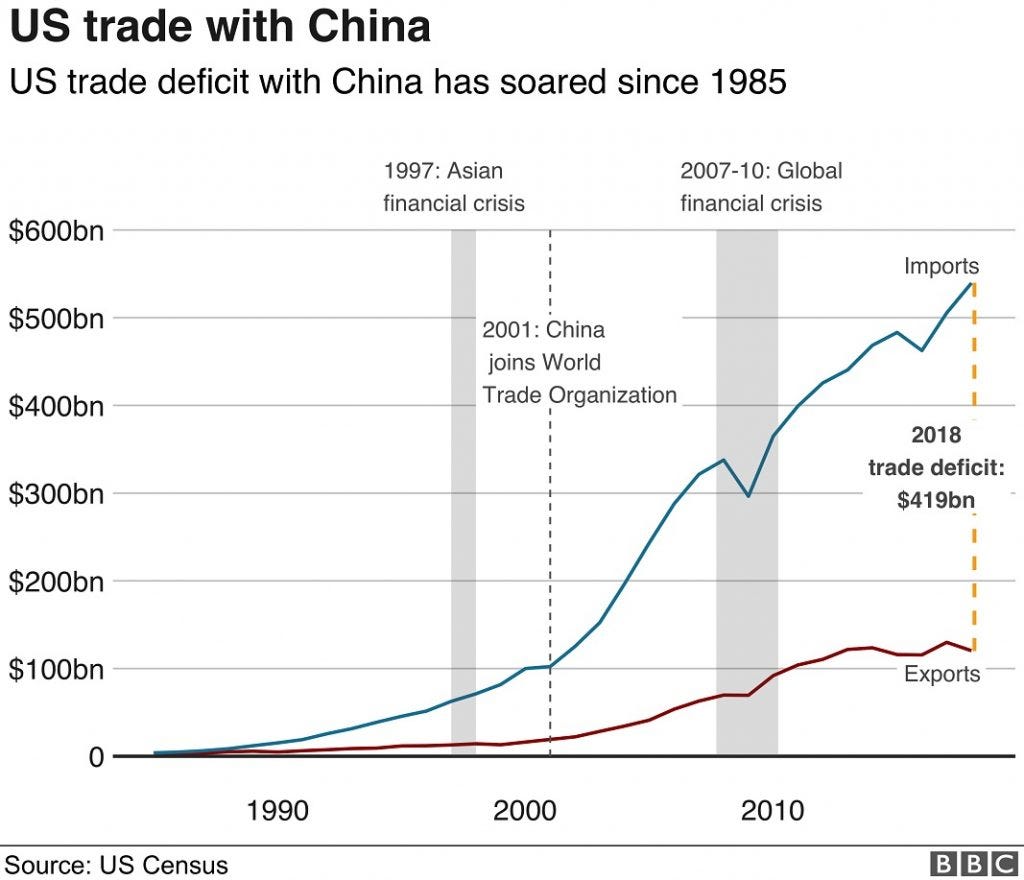

“Economically, this agreement is the equivalent of a one-way street.” With these words, Bill Clinton put on display the newest machine that would be integrated into the American capitalist labyrinth. The passing of the United States-China Relations Act of 2000 put America out of its legislative misery to trade with China, creating hope that the country would abandon its central planning and join free trade capitalism. Richard Nixon first flirted with normalcy by visiting in 1972. Jimmy Carter began the Sino-American project, and Bill Clinton gave it credibility. The world expected the storyline to continue.

However, just sixteen years later, the presidential frontrunner would accuse China of ‘the greatest theft in the history of the world.’ Donald Trump advocated for a better trade deal for American businesses and workers. He could no longer tolerate the manipulation of the renminbi, export subsidies, and lax standards that the Chinese exports exploited. He won.

Almost immediately, the United States entered into its trade war with China. The ripple effects of this were immense, proving to be a turning point in not just Sino-American relations but also in the intersection of geopolitics and trade. The biggest victim of this new line of protectionist policy was the World Trade Organization (WTO).

The two largest economies in the world, blatantly flouting the rules, drew the ire of other countries. The trade war that introduced the possibility of tariffs by the bastion of free trade eroded the credibility of its commitment to the very institution it built. This led to a wave of economic nationalism, and countries across the globe reconsidered their commitment to free trade.

The Trade Agreement At The End Of The Tunnel

Time and time again, we have seen the WTO failing to reach consensus at the most important times. Certainly, it has had its own share of victories, but it is often overpowered by these major shortcomings. Does this mean that globalization and rules-based trading draw to an end? That is impossible. It is simply an evolution in the world order. Today, we see newer countries emerging, like the BRICS nations, and the old hegemonies like the United Kingdom and France declining. Similarly, the WTO, which was created at the behest of this old order, is slowly becoming dysfunctional.

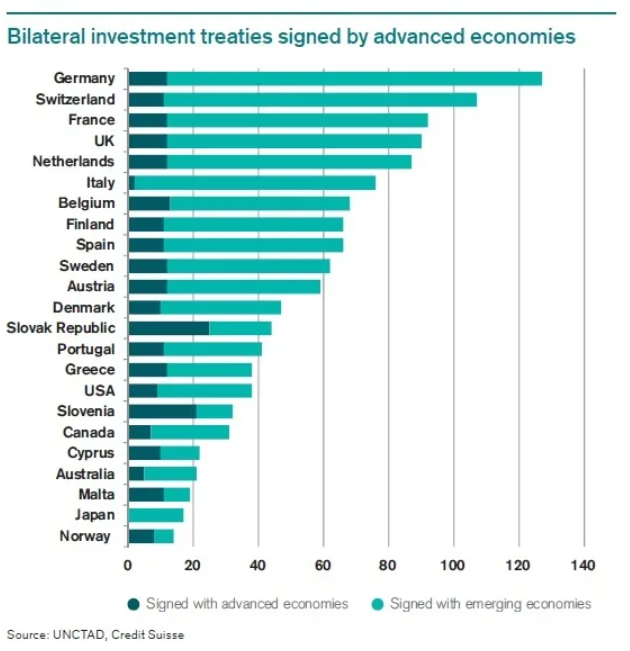

Ever since the failure of the WTO Doha Round, we have witnessed the rise in mega-regional and regional trade agreements. This system has seen neighbors unite through blocs like the EU, ASEAN, etc., to deal with large trading partners such as the US and China. Furthermore, these arrangements allow member countries to expand the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which has been stagnant since 1995. It also introduces geopolitics to the trade dynamic of the globe. As the intersection of trade and politics becomes increasingly nuanced, these agreements allow members to closely interact with allies while distancing themselves from foes.

This rationale was the force behind the mega-regional agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP, undergoing negotiations), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The CPTPP and T-TIP included the United States of America, and the excluded Chinese organized themselves through the RCEP. These regional trade agreements now constitute the most progress in trade between countries. Although they have their own shortcomings, these PTAs are a more efficient and dynamic form of economic cooperation while making use of basic standards of the WTO.

Take-Home Points

- The onset of the US-China Trade War has brought to light cracks in the rules-based regime of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

- The animosity between countries has reached such a high that the organization failed to concur on COVID-19 action and repeated its HIV failures.

- The appeals body of the WTO has been paralyzed by the United States, leaving international trade in the Wild West.

- WTO exists merely as a benchmark, and regional trade agreements take the lead in international trade.